The History of Zzap! 64 – Part 1

Genesis

Picture the scene. It’s the early 1980s and the home computer boom is exploding across the UK. From John o’ Groats to Land’s End, homes across the country are being invaded by ‘micro computers’ as thousands of British kids excitedly rip open the wrapping paper on a Christmas or birthday present to reveal a ZX Spectrum, Vic-20, Oric-1 or – if they were really lucky – a Commodore 64.

A computer (alongside the snooker table and BMX) was the most coveted present of the 1980s and many parents were more than happy to oblige their children. With little more than a vague notion that owning a computer would equip their beloved offspring with essential skills for life in the rapidly approaching C21st century, mums and dads across Britain parted with quite enormous sums of money (the price of a C64 in 1984 was £230 – the equivalent of £540 today!) to ensure that their son or daughter had a computer at home.

Of course, most teenagers only had one thing on their mind when it came to computers. Learning how to word process, produce a spreadsheet or build a database was no doubt a useful thing to learn, but most kids were interested in one thing – games. Just like the music business in the 1960s, the games industry of the 80s grew at a rapid rate. By 1984 the biggest selling computer games, such as Jet Set Willy and Daley Thompson’s Decathlon, were shifting hundreds of thousands of units and it was quickly evident that there was a lot of money to be made in the games industry. With sales of computer games growing exponentially it was no surprise that in 1984 dozens of new software houses sprang up and literally thousands of new computer games hit the shelves.

For the game hungry teenager this was both a blessing and a curse. The good news was that there were hundreds of new titles coming out every month. Never before had gamers had so many games to choose from. However, the bad news was that a very large percentage of them were absolute tosh. A number of publishers were guilty of churning out games to meet demand with little care for quality or the consumer. The average price of a game in 1984 was £6.50 - which was a good few week’s pocket money - so you had to be very careful. Many a cassette was adorned with awesome artwork that hid an awful game.

In this pre-internet era, game buying guidance was available in the form of computer magazines. Commodore User, Commodore Computing International and Commodore Horizons were the most widely read C64 magazines of the early to mid-eighties, whilst multiplatform magazines such as Computer & Video Games covered the ZX Spectrum, the BBC, the C64, the Amstrad and to a lesser extent the Oric-1 and Dragon 32. The quality of these magazines was mixed to say the least, with some having an almost ‘anti-games’ attitude. Commodore Horizons, for example, contained a thin smattering of half-baked game reviews reluctantly written by journalists who would probably have been much happier writing copy about circuit boards than zapping aliens.

The exception, in the early years, was Personal Computer Games. Launched in July 1983 this excellent magazine was devoted to the fledgling culture of gaming and - I think it’s safe to say - was the pioneer of the modern videogames magazine. Its writers were young, witty and, most importantly, understood and loved computer games. Personal Computer Games (PCG) was edited by Yeovil lad and publishing-millionaire-to-be-Chris Anderson. Yet, despite its brilliance, by February 1985 it had disappeared from the newsagents’ shelves for ever. Why PCG suddenly vanished is a bit of a mystery - one rumour was that a lack of advertising revenue had killed it off. Whatever the reason for its demise, it was a terrible shame and (as evident in the letters page of Zzap!64 issue one) gamers up and down the country were gutted.

As Chris cleared out his office, 150 miles away, in the sleepy Shropshire town of Ludlow, freelance artist Oliver Frey, Oli’s brother Franco and their business partner Roger Kean had recently founded the publishing company Newsfield. The origins of Newsfield Publications can be traced back to the late 1960s when Oliver Frey met Roger Kean at the London Film School. The two quickly became close friends but when the course ended in December 1970 each went their separate ways. Zurich born Frey, unable to get work in the film industry due to regulations over foreign workers, returned to Switzerland and Kean got a job as an assistant film editor at the BBC.

Yet the two weren’t parted for long. In the early 70s, Roger jacked in his job at the BBC and joined Oli in Switzerland. Together they spent a year trying to get a commercial film company up and running but were ultimately unsuccessful. In the end, Roger returned to England and resumed being a film editor while Oli remained in Switzerland drawing War Picture Library comic book stories for Fleetway Publications.

Again, the separation didn’t last long. Due to the exchange rate between Sterling and the Swiss Franc, Oli was getting less and less return for his work and decided to relocate to England where he was reunited with Roger Kean. The pair settled in North London and Frey found regular work as a freelance illustrator and worked for numerous publishers including IPC Magazines and Oxford University Press.

Throughout the seventies his reputation as an artist grew and the work he was commissioned to do became increasingly prestigious. He worked on ‘The Trigan Empire’ and ‘SOS International’ taking over from legendary comic book artist Don Lawrence; and then in 1978 his work reached a global audience when he provided the comic book art for the wonderful opening sequence to Superman: The Movie.

In October 1982 Oli and Roger left the hustle and bustle of London for the olde worlde country charm of Ludlow in Shropshire. A short while later they were joined by Oli’s brother Franco. Franco had developed an interest in the emerging home micro scene and was in contact with a German company who were keen to import ZX Spectrum games. Franco bought himself a Speccy to research the market and, as the three of them play tested games on Franco’s new computer, they had the idea of setting up a mail order service. A partnership was established in June 1983 and Oli was given the task of drawing illustrations for a magazine advertisement and mail order catalogue while Roger and Franco worked on the business side of things.

Roger and Oli were keen on short, sharp titles, and Kean — as a JG Ballard fan — had always liked the title Crash despite its rather negative computer connotations. A month later, the first ad for Crash Micro Games Action appeared, appropriately enough, in issue one of Personal Computer Games magazine.

Crash Micro Games Action was an instant success with the Spectrum community and within a few months the idea of turning the catalogue into a magazine was born. Crash was proposed to WH Smith, who immediately accepted and was duly launched on 13 January 1984 at a cover price of 75p.

With its rebellious attitude and brutally honest approach to games reviews, Crash was an instant success and within only a few months it was selling tens of thousands of copies per issue. Oli, Roger and Franco had come up with a winning formula; but not content to rest on their laurels, the Newsfield team looked around to see how they could expand and build on their accomplishments.

The most obvious opportunity beyond the Spectrum world was the rapidly growing Commodore 64 games scene. By 1985 gaming was growing quicker on the C64 than on any other computer on the planet, but existing Commodore mags were reluctant to take it seriously. Commodore User, Commodore Horizons and Your Commodore lacked both a genuine love of games and the energy and wit to write about them enthusiastically. In fact, other than Crash, the only computer magazine with a genuine love of gaming was Personal Computer Games, so it must’ve been a pleasant surprise when the Crash office phone rang one day in 1985 and on the end of the line was PCG editor Chris Anderson.

On hearing on the grapevine that Newsfield were thinking seriously of launching a C64 magazine, Chris rang Roger Kean from a phone box off Oxford Street and put forward himself as editor. His reasons were several, but principally 1) he was disenchanted with PCG’s publisher VNU; 2) he wanted to concentrate on a single format title; and 3) he hated the daily commute between Yeovil and the PCG offices in London. Roger and Chris discussed the possibility of Chris setting up Zzap! in Yeovil and soon after Chris resigned his PCG editorship and joined Newsfield. It was a great coup for the lads from Ludlow. PCG was a ‘real’ (London-based) magazine and Newsfield had been dubbed by EMAP as ‘rural pirates’. Chris wanting to join Newsfield was both a ringing endorsement and significant recognition of what the Crash team had achieved to that point.

After a few discussions, and an agreement to drop the originally suggested names of ‘Sprite and Sound’ and ‘Bang!’ (one idea was to have three magazines for the Speccy, 64 and Amstrad called Crash! Bang! and Wallop! respectively), Chris threw himself into his new post and within a couple of months Zzap!64 was born.

One of Crash’s unique features was to use school kids to review games. The thinking behind it being that reviews would be more credible if they were written by the kind of kids that were buying the games and that this would create a close relationship between the magazine and its readers. This worked surprisingly well in Crash, but Chris Anderson was adamant that the reviews in Zzap!64 weren’t going to follow the same pattern. Chris didn’t want Zzap to be written by reluctant game-hating ‘computer journalists’, but neither did he want a bunch of school kids piling into the office at half past three every day. Chris had brought reviewer Bob Wade with him from PCG, but he wanted two more writers so that each game could be reviewed by at least three people.

In the end, a solution was found in the form of two nineteen year olds who had recently been finalists in a PCG competition to find Britain’s greatest gamer. It was a perfect fit as they were both exceptional gamers and also displayed a flair for writing. Their names were Gary Penn and Julian Rignall. So, with experienced editor Chris at the helm and the enthusiastic review team of Bob Wade, Gary Penn and Julian Rignall in place, the job of bringing Zzap!64 issue one to life got underway in earnest.

Zzap!64 first hit the shelves on April 11th, 1985. The cover of Issue One featured a brilliant piece of Oliver Frey art depicting a scene from the game Elite, and the magazine enticed the would-be buyer with the promise of an ‘Incredible 50 pages of reviews’. Issue One was a mammoth 132 pages long and featured 39 game reviews. The highest scoring was Firebird’s Elite with 95% - Zzap’s first Gold Medal game - and the lowest was Activision’s Web Dimension with a paltry 27%. In addition to the reviews, Issue One featured:

●

a highly amusing letters page known as the ‘Zzap! Rrap’

●

the Zzap Challenge in which Julian Rignall defeated Gary Penn and Bob Wade at Impossible Mission

●

the Zzap!64 Top 64 (1. Boulder Dash, 2. Impossible Mission, 3. Decathlon, 4. International Soccer, 5. PSI Warrior)

●

A suitably off beat column by psychedelic programmer Jeff Minter

●

An in-depth article about the C64 games industry featuring David Tomkins from Commodore, Tim Chaney from US Gold, Ian Stewart from Gremlin Graphics and Andy Walker from Taskset; all of whom waxed lyrical about the 64’s capabilities and its rosy future

●

An interview with Tony Crowther which revealed that he didn’t actually play games and wasn’t very keen on Jeff Minter

●

A massive tips section which included beautiful maps of The Lords of Midnight and The Staff of Karnath

●

An article about music software which judged that Activision’s Music Maker was the best (85%) while Quicksilva’s Ultisynth (46%) left much to be desired

●

The White Wizard who provided the low down on the Adventure games scene

●

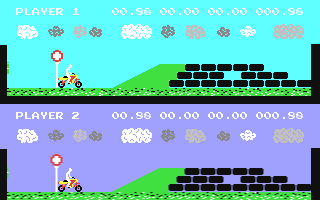

Zzap! Flash in which ‘Ed Banger’ revealed sneak previews of upcoming titles like World Series Baseball and Thing on a Spring as well as reporting that Boots had cut the in store price of the C64 by £80 to a more family budget friendly £150

●

And a little guy in the margins known as Rockford

Packed with content and bursting with a humour and energy that even made Crash look a little tame, it was 132 pages of brilliance.

Compared to its contemporaries, Zzap!64 was light years ahead. Like its big brother Crash, Zzap was designed to promote the thrill of playing games. From Issue One, games were scrutinised by two or three reviewers to present a balanced spread of opinion, and the very best games - the Gold Medals and Sizzlers - had colour coverage of two and sometimes three or four pages in length. Zzap! captured the spirit of a fanzine but had the substance of a professional publication, and while in the very early days it may have been a bit amateurish in places, it struck a chord with its readers who instantly fell in love with it. Somebody once said that a great magazine is like a good friend dropping by. I couldn’t agree more. Every month I looked forward to Zzap!64 turning up at my front door and I absolutely loved the time I spent reading it. It made me laugh, it made me think and it developed in me, at a young age, a love of reading which I have kept for the rest of my life.

So, there you are – Part One of my History of Zzap!64. I hope you enjoyed it. Join me next time when I’ll be looking at issues 2, 3 and 4. An era of great games – Pitstop 2, MULE, Dropzone, Way of the Exploding Fist and Beach Head 2 – but a tumultuous time behind the scenes with office relocation, editorial disagreements and … well you’ll just have to wait until next time to find out!

Martin C Grundy